Deputy Speaker of Parliament, Thomas Tayebwa, has urged private universities to prioritize groundbreaking research, warning that institutions focused solely on teaching risk becoming little more than glorified secondary schools.

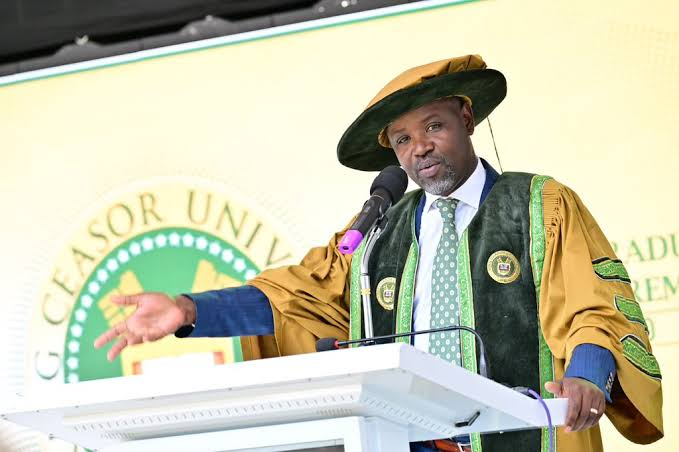

Speaking as the guest of honour at the 5th graduation ceremony of King Ceasor University in Bunga, Kampala, Tayebwa underscored the critical role of research in addressing Uganda’s development challenges.

“We do not want a university that only teaches; otherwise, you will be like a secondary school,” he said. “We need to see your groundbreaking research because the problems we have are unique and require unique solutions.”

Although Uganda has expanded access to higher education, research output remains disproportionately low—especially among private institutions.

According to the 2021 UNESCO Science Report, Uganda contributes less than 1% of Africa’s total research output. The majority of that comes from public institutions such as Makerere University, which has historically led the country’s academic research efforts.

In contrast, many private universities emphasize teaching, offering market-driven courses focused on employability, but often neglect investment in research infrastructure or full-time research faculty. A 2019 report by the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) found that out of more than 40 licensed private institutions, fewer than 10 had published significant peer-reviewed research in the preceding two years.

Experts warn that this imbalance limits the country’s innovation potential and undermines the role of universities as engines of knowledge generation.

Tayebwa encouraged private institutions to take advantage of the government’s growing—but still limited—interest in supporting research.

“The government’s investment in research might not be sufficient for now, but it is a good gesture. I encourage King Ceasor University to compete for such funds,” he said.

Uganda’s research funding landscape remains modest but is slowly evolving. Historically, the bulk of research funding has come from international donors such as USAID, NORAD, and the World Bank. According to the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST), over 70% of all research projects in Uganda are donor-funded.

Domestically, however, the government has taken steps to bolster local research through the creation of the Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) Secretariat under the Office of the President. The STI oversees the Research and Innovation Fund (RIF), which has so far supported hundreds of projects, particularly in agriculture, health, and ICT—mainly through public universities like Makerere.

Private universities, however, continue to receive a negligible share of this support, hindered by limited research infrastructure, fewer PhD-qualified faculty, and reduced capacity to compete for grants.

Tayebwa also emphasized the importance of mentorship in academia, stating that cultivating future researchers and academics will have a lasting impact on the quality and legacy of institutions.

He pledged continued government support for private universities, acknowledging their role in complementing public institutions and broadening access to higher education.

“As a government, we shall give you all the necessary support to ensure that you continue complementing us in our work,” he said.

Dr. Chris Baryomunsi, Chairperson of the University Council and Minister of ICT and National Guidance, revealed that King Ceasor University is exploring the introduction of postgraduate and doctoral programs.

“We are creating partnerships with other universities to facilitate the meaningful transfer of skills and knowledge and to improve the quality of education,” Baryomunsi said.

Uganda’s development challenges are both complex and context-specific. From youth unemployment to climate-induced agricultural losses, these issues require local solutions that imported research cannot always provide. Universities, especially those embedded in the communities they serve, are best positioned to generate these solutions.

Consider agriculture, which employs more than 70% of Ugandans. Despite its importance, productivity remains low due to factors such as climate variability, soil degradation, and limited mechanization. Homegrown research into drought-resistant crops, affordable irrigation technologies, and post-harvest storage methods could significantly improve rural livelihoods.

In a world growing more uncertain, research is not a luxury—it is a necessity.

Tayebwa’s call to private universities is, ultimately, a call to national service: to move beyond teaching and become engines of innovation and problem-solving for Uganda’s future.