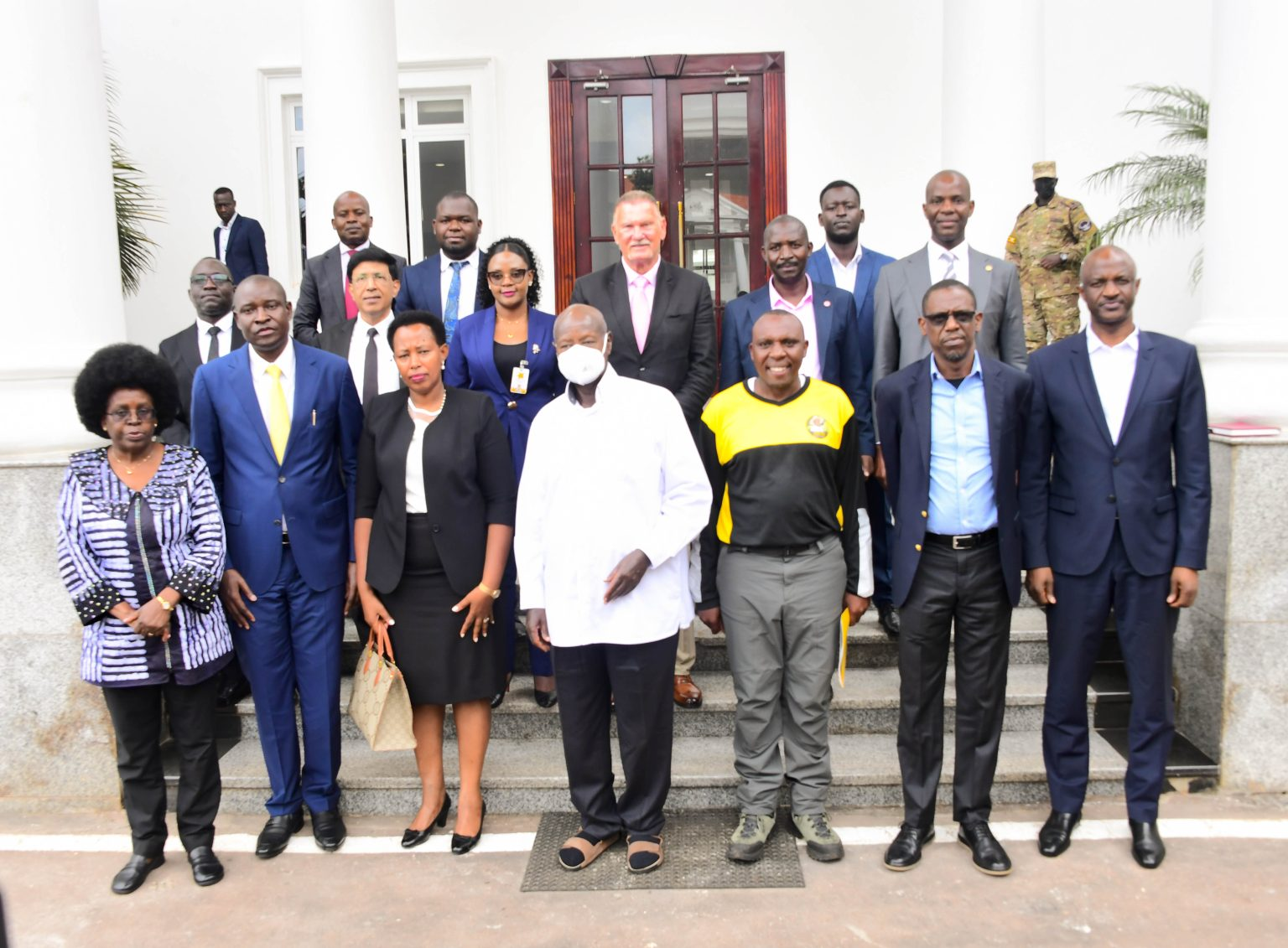

When President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni welcomed Ugandan scientist Dr. Mathias Magoola to State House Entebbe, the meeting signaled more than a ceremonial nod to science. It marked a convergence of innovation, national ambition, and global health—centered around one of the most audacious medical breakthroughs to emerge from the Global South: a gene-editing-based cancer therapy developed and patented by a Ugandan, with plans for global production based in Matugga, just outside Kampala.

This achievement—a U.S. patent for a treatment utilizing a guided RNA-Cas9 complex to target and disable cancer-causing genes—positions Uganda not merely as a consumer of advanced medical technologies but as a potential pioneer in the future of global oncology.

“This is not just a scientific breakthrough; it is a humanitarian contribution aimed at eradicating cancer globally,” Dr. Magoola told President Museveni. “The treatment is designed to be simple, affordable, and accessible, especially for developing countries.”

Granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on February 6, 2025, Dr. Magoola’s innovation leverages the CRISPR-Cas9 technique to edit mutated genes in cancer cells. What sets his approach apart, he says, is its versatility across all cancer types and stages, and its precision in sparing healthy cells—an elusive goal for conventional therapies like chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy.

If proven effective, the therapy could place Uganda among a select group of nations contributing to the frontier of cancer treatment. But its potential extends well beyond scientific achievement. Dr. Magoola plans to manufacture the therapy at Dei BioPharma’s upcoming drug and vaccine plant in Matugga—marking Uganda’s first major foray into high-value pharmaceutical production.

“All details of the manufacturing process are complete,” he said. “We are now preparing to submit our FDA approval plan, with clinical trials expected before the end of the year.”

The $300 billion global cancer therapy market—currently dominated by U.S., European, and Chinese companies—presents Uganda with a rare opening to establish itself in the high-stakes world of biotech. But this opportunity comes with equally high demands: delivering on efficacy, navigating stringent regulatory frameworks, and meeting world-class standards in production and scale.

While the science may be disruptive, sustaining progress will require a coordinated national ecosystem—one that integrates scientific governance, financial investment, and regulatory sophistication.

Like many low- and middle-income countries, Uganda faces significant gaps in the infrastructure required to support advanced biomedical innovation. The regulatory framework for overseeing complex interventions like gene and cell therapies remains underdeveloped. Clinical trial networks are still in their infancy, with limited capacity for standardized patient recruitment and protocol enforcement. Laboratory facilities for gene-based quality control and post-market surveillance are sparse. Moreover, weak enforcement of intellectual property rights and rudimentary systems for technology transfer continue to deter investment and hinder scalability.

Even with FDA approval on the horizon, turning this innovation into a globally distributed treatment will require strategic partnerships—likely with multinational biotech firms, global health organizations, or academic research consortia.

“This is our opportunity to lead in science, not just follow,” said Dr. Monica Musenero, Uganda’s Minister of Science, Technology, and Innovation. “But it will require alignment between government, the private sector, and global regulators.”

At the heart of this vision is Matugga—the future home of the multi-billion-dollar Dei BioPharma manufacturing facility, which aims to produce not only cancer therapies but also vaccines, antiretrovirals, and other essential medicines.

This move toward domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing is a deliberate pivot—born from the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic, which revealed Africa’s vulnerability to global supply chain disruptions and vaccine nationalism.

If successful, Matugga could emerge as a continental hub for biomanufacturing: reducing reliance on imports, creating skilled jobs, and symbolizing scientific self-reliance for the Global South.

“This is about shifting from being aid-dependent to knowledge-exporting,” said Ramathan Ggoobi, Secretary to the Treasury, who attended the State House meeting.

Still, building a resilient biotech ecosystem takes time. It demands talent retention, strong intellectual property protections, and sustained public-private collaboration—factors that remain fragile within Uganda’s innovation landscape.

Dr. Magoola’s cancer therapy arrives at a pivotal moment, as Uganda seeks to position itself as a leader in scientific diplomacy and regional innovation. Yet there’s a real risk that such a transformative innovation could be stalled by bureaucratic inertia, inadequate oversight, or political missteps.

This is Uganda’s moment: to leapfrog traditional barriers and offer a meaningful contribution to one of humanity’s most urgent health challenges.

It is also a test—of Uganda’s ability to support its innovators, build credible institutions, and turn homegrown breakthroughs into global solutions.

The idea of “healing the world from Matugga” is no longer a distant dream. It is now a bold, plausible proposition. But to realize it, Uganda must prove that its science is not only groundbreaking—but also sustainable, ethical, and scalable.

“This invention,” said Dr. Magoola, “is not just for Uganda. It is for the world. And we are ready to lead.”